Pronghorn herd near the Granite Mountains, Wyoming. In 1922, there were about 30,000 pronghorns in the American West. Thanks to enlightened management in several states, the populations had risen to 380,000 by 1964. (Photo copyright 2015, Chris Madson, all rights reserved)

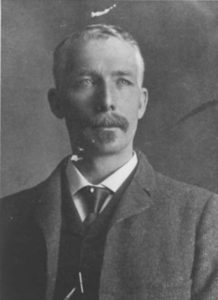

ON FEBRUARY 1, 1902, DAN NOWLIN BECAME CHIEF GAME WARDEN FOR THE STATE OF WYOMING. NOWLIN WAS A PRODUCT OF THE WESTERN frontier. Born in Kerr County, Texas, in 1857, he joined the Texas Rangers in 1873 at the age of sixteen. In 1888, he was elected to a two-year term as sheriff in Lincoln County, New Mexico, following the famous lawman, Pat Garrett, in that post. Eventually, he moved to Wyoming Territory to start a ranch in the as-yet-unsettled country along the upper Green River.

In his first year as Wyoming’s game warden, he traveled more than 1,000 miles on horseback to contact his deputies and inspect game herds, a feat he seemed to accept as a routine part of the job. During an eventful life, he’d faced renegade Comanches and Kiowa, tracked down rustlers and robbers, and built a home in some of the last wilderness of the West. He wasn’t daunted by the challenges of enforcing the emerging precepts of wildlife conservation on the frontier. What he seemed to find most discouraging was the task of convincing state lawmakers to fund the conservation effort with the hunting license money it raised.

In his 1902 report to the legislature, he had this to say: “Since the present game law has been in force— four years— non-resident hunters have paid into the State game fund, in round numbers, twenty-four thousand dollars; and a conservative estimate of the amount paid by them to citizens of Wyoming for guiding, equipment, etc., places the sum at one hundred and seventy-five thousand dollars. The sport and profit derived by our own citizens from our wild game during this period cannot be estimated; the expense to our taxpayers has been nil— not a dollar has been appropriated to assist in protecting our game.

“. . . [S]ince the date of my appointment . . . there were unpaid claims . . . aggregating nearly three thousand dollars. These claims were compelled to await payment until the State game fund had been replenished by the contingent moneys derived from the sale of hunting licenses, and from fines.

“The diversion of so much money from a fund that is inadequate at best has greatly crippled the service; notwithstanding this shortage of funds much effective work has been done. . . .”

In 1902, Wyoming collected $7,439.65 in hunting license fees and fines, but the legislature saw fit to spend only $4,184.50 on game. The lawmakers looked on income from hunting licenses as no different than any other revenue stream: When they saw a little black ink in the state’s ledger, they were inclined to approve a little more budget for the game warden; when times were lean, they were happy to divert the lion’s share of license fees away from game management to other priorities.

Nor was Wyoming in any way unusual in this. Most infant wildlife departments lived the same sort of street urchin’s existence, tending game populations that raised a tidy sum in license fees and economic benefits, then begging their masters for a pittance to support the work.

In 1907, the Pennsylvania state treasurer decided that a law granting the fines from all game law violations to the Game Commission was inconvenient, so he deposited them in the state’s general fund instead. In 1913, the Pennsylvania Game Commission managed to convince the state legislature to require all resident hunters to buy a $1 license, but in 1922, the newly elected governor, Gifford Pinchot— the same Pinchot who had helped Teddy Roosevelt establish the U.S. Forest Service— decided to channel all the license funds into the state’s coffers and fund the department with legislative appropriations.

In 1927, the director of the Colorado Game and Fish Commission headed off a similar effort. “They tried to take our game cash fund from us,” he wrote to a friend in Utah, “ which is money paid in licenses and things of that sort and belongs really to the sportsmen, but they were trying to put it in the general fund to appropriate as they pleased.”

The uncertainty of the financial support for state wildlife work may have been even more damaging than the paltry sums that were often granted to game managers by their legislatures, since they disrupted any plan that involved more than a year’s work. And lack of money was just one of the problems facing early conservationists. Once state wildlife departments began paying salaries to their employees, the jobs themselves often became embroiled in politics.

In 1931 Gifford Pinchot returned for a second term as Pennsylvania governor and set off another round of controversy by interfering with the Game Commission’s firing of four employees. Perhaps the most egregious example of pork barrel politics in state wildlife agencies came two years later in Missouri. A newly inaugurated governor chose Wilbur Buford, a politically connected attorney from St. Louis, as the state’s new commissioner of game and fish. At the end of his first year in office, Buford reported that he had accomplished a complete turnover of department personnel.

As the conservation movement gained momentum through the last half of the nineteenth century into the first decades of the twentieth, the use of jobs as rewards for party stalwarts, the back-room redirection of license income and fines collected from poachers were the rule, not the exception, in state wildlife agencies. If reports of specific cases seem to be scarce, it’s simply because there was nothing unusual in these maneuvers— they were the tools of the political trade at the time.

The pioneering wildlife advocates who built the first state conservation departments were well aware of the political landscape in which they operated. Joseph Kalbfus, the director of the infant Pennsylvania Game Commission at the turn of the last century, was not alone in preferring a guaranteed appropriation from the legislature for wildlife conservation rather than supporting it with hunting license dollars, but across the country, wildlife advocates found that no other funds were forthcoming. In most cases, these pioneer conservationist had manipulated the system to enact wildlife laws and create agencies to enforce them. But they quickly recognized that, without some insulation from the vagaries of politics, conservation would make no headway, and the only dependable source of income were the fees paid by hunters and anglers.

Reform proceeded slowly at first, as powerful sportsmen’s groups in a handful of states brought pressure to bear on legislatures to fund conservation departments and stay out of their personnel decisions.

Finally, in 1928, John Burnham, president of the American Game Association, stood up in front of the 15th American Game Conference in New York and made a proposal. He pointed out a variety of problems that faced wildlife conservation and outdoor recreation: loss of habitat, the effects of increasing human population and demand for hunting, limited access to recreation on public and private land. And the lack of adequate funding for the enforcement of game laws, wildlife management, and research.

Burnham suggested that the country needed an overarching policy to guide the management of wildlife and wildlife-related recreation. The assembly agreed and a twelve-man committee was formed to draft a statement of goals for review at the next annual meeting. The committee was chaired by an itinerant biologist who had recently left the U.S. Forest Service to begin a survey of game populations in the upper Midwest— Aldo Leopold.

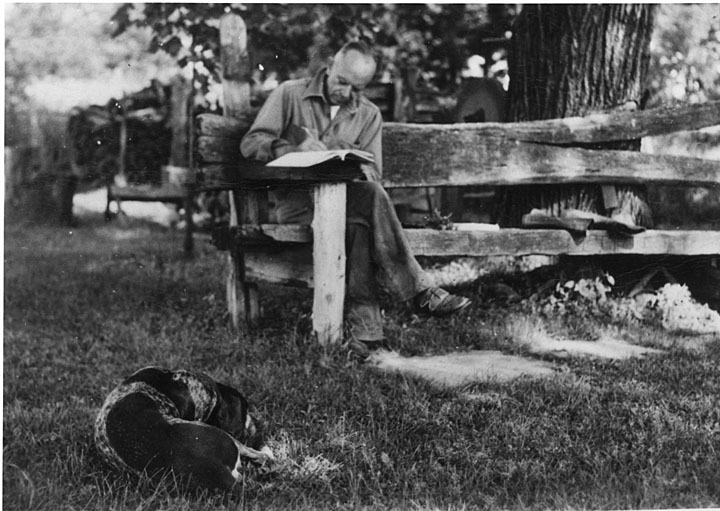

Aldo Leopold making an entry in his journal at his shack in Wisconsin. Leopold chaired the committee that wrote the American Game Policy and was probably its primary author.

Leopold had been instrumental in reforming the state wildlife agencies in New Mexico and Wisconsin, and his experience with the game survey would soon prompt him to write the pioneering text, Game Management, a classic in its field. He was the perfect choice to lead the effort to define the needs of the struggling conservation movement.

He defined the committee’s goal with disarming simplicity: “This is a plan for stimulating the growing of wild game crops for recreational use,” he wrote. “While this plan deals with game only, the actions necessary to produce a crop of game are in large part those which will also conserve other valuable forms of wild life.”

The committee spent two years hammering out the details and came to the 1930 American Game Conference with a final draft. There is no record of the debate that ensued or a count of the final vote, but in the end, the professionals in attendance adopted the proposal.

The American Game Policy was a wide-ranging document. It pointed out that “our present attempt to restore game by the control of hunting seasons and bag limits alone has failed”— and called for active management “to provide favorable environments” for game on the modern landscape. It discussed ways to encourage private landholders to help create and maintain habitat, advocated a drastic increase in funding for research, and called for “harmonious cooperation between sportsmen and other conservationists.”

After considering the major ecological and political issues facing wildlife, the committee turned its attention to the emerging profession of wildlife management. The members emphasized the need for technically trained biologists, wildlife administrators, and field workers along with national funding for wildlife research. They also called for reorganization of state conservation departments.

The first step, in their view, was establishing a policy-making body that had some degree of independence. The members of this commission would be appointed by the governor; they would serve without pay, and their terms would be staggered “to avoid sudden reversals in policy.” This commission would have the power to set all hunting and fishing regulations, and it would hire the department’s director. “If this vital point is compromised,” the policy stated, “the whole idea breaks down.”

The director would hire all department personnel and be responsible for the execution of all management and enforcement. The commission should avoid “meddling in executive detail”— according to the authors of the game policy, “This is always fatal.”

The game policy went on to call for an increase in the price of hunting and fishing licenses. “It goes without saying,” the authors wrote, “that in no case should the sportsmen tolerate diversion of a single dollar of state game license funds for general state purposes.”

These recommendations weren’t pie-in-the-sky ideals; they were based on seventy years of hard experience. And, for the most part, they worked.

Mule deer on wheat stubble north of Burns, Wyoming. (Photo copyright, 2018, Chris Madson, all rights reserved)

Numbers can be hard to come by, but consider some of these population estimates: In 1940, there were about 22,000 elk in Montana outside of Yellowstone; in 1951, there were 40,000, and in 1978, 55,000. Managers in Idaho have estimated that the state’s deer population was about 45,000 animals in 1923; by 1963, it had increased to 315,000. In 1925, Missouri officials estimated the state’s deer population at around 400; by 1944, it had grown to 15,000, and today, it stands at about 1.4 million. In 1927, writer and conservationist Nash Buckingham concluded that “the wild turkey is in a critical situation through most of its present range”— in 1952, America’s turkey population was estimated at more than 320,000 birds, and today, it is over five million. In 1931, there were thirty-five trumpeter swans left in the world; in 1957, the population had grown to almost 500, and today, it has grown to more than 63,000. The populations of most wild animals in North America, game and nongame, followed a similar trend through the middle of the twentieth century.

And so sportsmen and other conservation-minded members of the public coasted through three generations of wildlife prosperity, beneficiaries of a policy most of us have forgotten and none of us appreciated. As active support from conservationists waned and fragmented, the back-room politicians decided to re-assert themselves. Bit by bit, one bad decision at a time, they started to meddle in the organization of wildlife agencies.

It began with moves to consolidate state agencies with broadly environmental missions. In the 1930 game policy, the Leopold committee had good things to say about “coordination of forestry, game, fish, and parks, and other related activities,” but the move toward departments of natural resources that began in the 1970s departed from the game policy’s recommendations in important ways. These mergers often eliminated the independent wildlife commission or buried it in bureaucracy. The independent director was also buried and found himself reporting to one or more high-level administrators who owed their positions to the governor, not an independent commission of unpaid citizens with a special interest in wildlife.

And the crucial distinction between income from sportsmen’s licenses and legislative appropriations was sometimes blurred. When Kansas decided to merge its wildlife agency with its parks department in the 1980s, this confusion led to several years of misappropriation of federal wildlife aid. When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service discovered the violation of the Pittman-Robertson Act, it required the state to return all the misused funds before it received any P-R dollars. The process took years of budget belt-tightening to complete.

Bighorn sheep in the Platte River Canyon, Wyoming. Recovery of bighorn populations has been almost entirely due to the efforts of state wildlife agencies, in cooperation with private-sector conservation groups. (Photo copyright 2017, Chris Madson, all rights reserved)

In some states, the commission’s authority to hire the wildlife department’s top administrators is eroding. In 1995, the Wyoming legislature gave the governor authority to appoint the department’s director, and since then, the list of “at-will” employees in the department has been expanded to include deputy directors and division chiefs. In Montana, the director of the Fish, Wildlife and Parks department is part of the governor’s cabinet and serves at his pleasure. In Kansas, the secretary of the Wildlife and Parks Department is appointed by the governor. It’s the same in at least four other states.

The revenue from sportsmen’s licenses continues to be earmarked for wildlife work, although state legislatures occasionally consider proposals that would redirect this income to other uses, even to this day. One pivotal element of the Leopold committee’s blueprint for state wildlife agencies was that “the public should help bear those costs which affect the public interest,” including research, general habitat protection, and wildlife education. A handful of states— Missouri, Arkansas, Colorado, and Arizona— have adopted laws that guarantee their wildlife departments a small percentage of sales tax revenue or income from lotteries, a commitment from the non-sporting public the original game policy committee would have applauded, but most state wildlife work still depends on funding from license sales and excise taxes on arms, ammunition, and fishing tackle.

Even as the scope of conservation challenges expands, state legislatures seem less and less inclined to consider earmarked funding for wildlife, whether the money comes from a license fee increase or a tax. When the lawmakers decide to throw a bone to conservation, they prefer to support one-year appropriations. This works fine for short-term projects like building hatcheries or buying a specific tract of habitat, but when the appropriations support ongoing management efforts, there is a constant risk that the job will be disrupted before it’s finished, either because a legislator has found another pet project or because he has an ax to grind.

State agencies are created to serve their constituents. The process is inherently political. There’s no way to completely insulate a state wildlife agency from political influence, and even if there were, it would be a bad idea to do it. But almost a century ago, the conservation community recognized that wildlife management in the states couldn’t survive the constant buffeting of statehouse politics. Leaders of the movement found a way to guarantee that the people retained a voice in the discourse on wildlife matters while wildlife managers maintained some measure of consistency in their programs, personnel, and funding.

The authors of the 1930 American Game Policy conceded that, when it comes to effective conservation work, “the attitude of the public, the governor, and the legislature counts for more than the form of organization.” But, they continued, “given the right attitude, there is such a thing as a best form for a state conservation department.”

The system they outlined may well have been that “best form,” or something very close to it. Based on three generations of experimentation and the collected wisdom of the nation’s most experienced wildlife professionals, it worked well in state after state as it was adopted in the 1930s and 1940s, and it can work just as well today— when it’s given a chance.

The reorganizations of state wildlife agencies across the country, the increase in “at-will” employees, the refusal to dedicate revenue from the general public for conservation work are largely the work of people with no stake in the agencies or their mission. They undermine wildlife management when we need it most. Before we tear down the system that has served us so well for so long, it would seem wise to get answers to a simple question: Why mess with success?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.