The rise of the land ethic

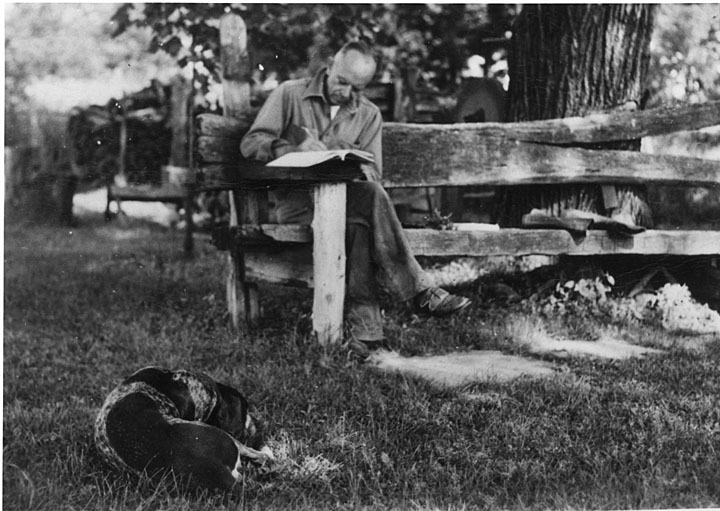

THE SUMMER OF 1947 WAS QUIETER FOR ALDO LEOPOLD THAN HE’D EXPECTED.

He was at the peak of a remarkable career: founder and chair of the world’s first department of wildlife management at the University of Wisconsin; a sought-after essayist and public speaker; one of the founders of the Wilderness Society; honorary vice president of the American Forestry Association; and president of the Ecological Society of America, elected even though he seldom attended the ESA’s annual conference and did not consider himself an active member.[i]

He was also wrestling with a manuscript for a nature book he’d promised the editors at Alfred A. Knopf. It was a project he’d been considering for six years and had discussed with Knopf for at least three.[ii] The book project had proven to be unexpectedly challenging — the wordsmiths at Knopf struggled with the eclectic nature of the essays he submitted, some intensely personal and descriptive, others expansive and deeply philosophical.[iii] And Leopold couldn’t find the time to give the work his undivided attention.

It took a doctor’s order to slow him down. Sometime in late 1945, he had begun suffering occasional spasms of extreme pain on the left side of his face. At some point, he sought medical attention and was given a name for the problem— trigeminal neuralgia— and few options for treatment. By early 1947, the attacks had become frequent and temporarily debilitating. In May, he submitted to an “alcohol block,” an injection his doctors hoped would deaden the trigeminal nerve. The specialists weren’t sure how precise the injection would be, how much it would relieve the pain, or how long the effect would last, but, short of surgery, it was the only palliative they could offer. They cautioned their patient to step back from his hectic schedule and rest over the summer.[iv]

With those directions in mind, Leopold scheduled just a single June trip to Minnesota where he attended the Wilderness Society’s annual council meeting and stopped in Minneapolis on the way back to address the conservation committee of the Garden Club of America, a speech he called “The Ecological Conscience.” With those commitments fulfilled, he settled down to prepare his essays for publication.[v]

Sometime in late July, as the painful spasms in his face returned and he reflected on a lifetime spent in defense of wildlife and wild land, his thoughts turned back to something he’d said to the Garden Club. It reflected a broadening of the precepts he’d been taught as a student in Gifford Pinchot’s School of Forestry at Yale; in the subsequent thirty-eight years, he had reached beyond purely technical analysis and Pinchot’s utilitarian “wise use” of natural resources to a philosophical whole that combined ecological reality with human morality.

“Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient,” he wrote. “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community; it is wrong when it tends otherwise.”[vi] He called this “the land ethic.”

It was— and remains— one of the great ideas in American thought, and, like most great ideas, it wasn’t entirely original. Its roots reached back across the generations to the experiences of the first generation of Europeans to settle in the New World.

As early as 1626, the residents of New Plymouth, Massachusetts, adopted a local ordinance to protect the colony from the “inconveniences as do and may befall the plantation by the want of timber.” Before a colonist cut down a tree, he was required to seek “the consent approbation and liking of the Governour and council.”[vii] And the colonial concern over impending scarcity wasn’t limited to lumber. In the winter of 1646, the council of the settlement of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, ordered “that there shalbe noe shootinge of deere from the first of May tell the first of November and if any shall shoote a deere with in that tyme he shall forfitt 5 pounds.”[viii]

The discovery was repeated again and again as each generation of emigrants ventured into territory they considered to be unsettled, built their cabins, and lived off the fat of the land while they labored to transform it. As stands of old-growth white pine, chestnut, and oak melted away under the onslaught of the timber barons, as populations of bison and elk disappeared at the edge of the frontier and the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet began their free fall toward extinction, the idea of a more judicious approach to the management of natural resources steadily gained public support.

And so Americans began to organize. The trend began among zoologists and enthusiasts of natural history: the American Fisheries Society in 1870;[ix] the American Forestry Association in 1875;[x] the Nuttall Ornithologists’ Club in 1873, which became the American Ornithologists’ Union in 1883;[xi] the Boone and Crockett Club, a gathering of influential patrician sportsmen and scientists, in 1887.[xii]

In February of 1886, George Bird Grinnell, editor and publisher of Forest & Stream magazine, called for “an association for the protection of wild birds and their eggs, which shall be called the Audubon Society.”[xiii] Within three years, membership in the society had grown to more than 50,000.[xiv]

In response to a groundswell of public concern, the federal government began to act. Congress created a division of fisheries management in 1871, a division of forestry in 1881, and a division of economic ornithology to research the practical benefits of songbirds in 1885. The first national forest was established in 1891; the first national wildlife refuge, in 1892. In 1890, it became illegal to “throw rubbish, filth, refuse, or waste of any kind into the navigable rivers of the United States.”[xv] By the time Teddy Roosevelt moved into the White House a decade later, the electorate had clearly demonstrated its support for practical conservation, and the government’s role in advancing the doctrine had already become a prominent part of the nation’s political dialogue.

As the currents of pragmatic management of natural resources gathered force, another school of thought also developed. While Pinchot stressed the importance of use in his approach, his contemporary, John Muir, championed a less utilitarian relationship between humans and wild places: “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul,” he wrote in 1912[xvi]

The antecedents of Muir’s view stretch back as far the origins of practical conservation. Its origins can be traced through the popular writings of John Burroughs; through the work of artist-naturalists like Audubon, Alexander Wilson, and Mark Catesby; into the musings of Henry David Thoreau— “In wildness is the preservation of the world”;[xvii]— and even earlier in the journals of men who are now largely forgotten, pioneers like John Lawson— “. . . the loftiest Timbers . . . proper Habitations for the Sweet-singing Birds . . .”[xviii] and Thomas Morton— “’Twas Nature’s Masterpiece . . . If this land be not rich, then is the whole world poore.”[xix]

This less pragmatic ideal found its way into federal policies even before the more practical approaches to conservation were adopted. As the Civil War raged to its conclusion in 1864, President Lincoln took time to sign a grant of land to the state of California, a parcel “known as the Yo-semite valley . . . with the stipulation . . . that the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation . . . for all time.”[xx] Eight years later, Congress voted to set aside a much larger tract of land “lying near the Head-waters of the Yellowstone River . . . as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”[xxi] Just what constitutes a “pleasuring-ground” remains the subject of heated debate in some circles even today, but by the time the National Park Service was formed in 1916, it was clear that at least part of Yellowstone’s purpose was to serve as a refuge for wildlife as well as people.

Esthetic and even spiritual sentiments had drifted in and out of the developing canons of practical conservation for generations before Leopold was even born, and the trendrils of such perceptions reached back across the Atlantic, disappearing at last into the mists of prehistory in the Old World. What Leopold added was a stiff shot of ecology. Along with other scientific pioneers like Charles Elton and Herbert Stoddard, Leopold had stepped back from the disciplines of zoology and natural history to consider the processes and interactions that drive natural systems. His land ethic combined the scientific, practical, and esthetic elements of the conservation imperative and did it with a grace and poetic economy that was unprecedented.

It was a lucky thing for those of us who came after that he found the respite to finish his work that summer. By August, the neuralgia had intensified to the point that Leopold scheduled surgery to have the trigeminal nerve severed. The surgeons at the Mayo Clinic declared the procedure a success, but it left him with partial paralysis on the left side of his face, difficulty speaking, a chronically dry left eye, and, most disturbing, problems with his memory. While he recovered slowly, finally resuming his normal lecture schedule and contributing to a few technical conferences the following spring,[xxii] he managed to write only two more short essays for the book before his death on April 21, 1948, at the age of sixty-one.[xxiii]

Knopf dropped the book before Leopold’s death, but thanks to Leopold’s son, Starker, Oxford University Press picked it up,[xxiv] and after the family and several of his close friends finished the final editing, the collection appeared under the title, A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There, in 1949.[xxv]

It’s an interesting footnote to history that several editors were uncomfortable with the philosophical essays Leopold had included in Sand County. They saw more market value in the nature vignettes that made up the almanac itself. In retrospect, it was precisely the philosophy that led to its initial success and has accounted for its ongoing popularity. Even more than Silent Spring, Sand County’s “Sketches Here and There” and “The Upshot” were the new testament of environmental stewardship in America. They crystallized the sentiment that had shaped almost a century of action by the government, the scientific community, a host of organizations, and millions of Americans.

Whenever energy began to flag, people were goaded by another in a succession of sobering natural catastrophes: Wisconsin’s Peshtigo fire in 1871, a hurricane of flame that claimed the lives of at least 1,500 people; the “Big Burn” of 1910, another inferno that laid waste to an area the size of New Jersey and killed 85 people in just two days; the Galveston hurricane in 1900 that erased a city and killed between 6,000 and 12,000 people; the Mississippi Flood of 1927; the Dust Bowl; rivers catching fire in major urban areas; high-profile animals like the bald eagle and whooping crane leading scores of other species on the way toward extinction, all of them reminders of the consequences of a failure to understand and respect the land and the processes it supports.

The momentum that had driven the growing environmental movement through the last third of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth reached some sort of peak in the decades following the appearance of Sand County. A groundswell of support led to federal laws that promised to control air and water pollution, imposed limits on pesticide use, protected endangered species, reduced erosion on vulnerable cropland, established wildlife habitat there, and mandated a thorough review of the consequences of any major federal development project before it could begin. The Land and Water Conservation Fund was established in 1964,[xxvi] a program that diverted billions of dollars of income from offshore oil leases to projects as diverse as improving water treatment plants and expanding national parks and wildlife refuges, and the Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1970.

Other programs emerged in the same era, arguably less pragmatic but solidly in the tradition of the esthetic and spiritual concerns captured in Leopold’s land ethic: the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, the Marine Mammals Protection Act of 1972, the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 1960, and the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in 1980, legislation that added nearly 44 million acres to the national park system, almost 10 million acres to the nation’s wildlife refuges, and more than 9 million acres to the area of federally protected wilderness. There was every reason to believe that Americans were unalterably committed to a sustainable relationship with the land they called home.

NEXT INSTALLMENT: THE TIDE GOES OUT

[i] p. 493. Meine, Curt, 1988. Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

[ii] p.460 ff.

[iii] p. 485-486.

[iv] p. 477 and 497.

[v] p. 497-498.

[vi] p. 500-502.

[vii] p.28. The Compact with the Charter and Laws of the Colony of New Plymouth: Together with the Charter of the Council at Plymouth and an Appendix. Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State, Boston, MA, 1836. From Laws of the Colony of New Plymouth

[viii] Brigham, Clarence, S., ed., 1901. Early Records of the Town of Portsmouth. E.I. Freeman & Sons, State Printers, Providence, RI. p.34.

[ix] https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/fisheries/new+site+links/REFLECTIONS-the+history+of+AFS.PDF. Accessed April 20, 2018.

[x] Steen, Harold K., 2004. The U.S. Forest Service: A History. Forest History Society in association with the University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA. p.9.

[xi] Orr, Oliver H. Jr., 1992. Saving American Birds: T. Gilbert Pearson and the Founding of the Audubon Movement. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, FL. p.22.

[xii] Reiger, John F., 2001. American Sportsmen and the Origins of Conservation. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR. p.4.

[xiii] Grinnell, George Bird, 1886. “The Audubon Society” in Forest and Stream: A Weekly Journal of the Rod and Gun, Vol. 26:3, p.41, Feb. 11, 1886.

[xiv] Trefethen, James B., 1975. An American Crusade for Wildlife. Winchester Press, New York, NY. p.130.

[xv] Statutes at Large of the United States of America, Volume XXVI. Fifty-first Congress, Session I, Chapter 907, 1890. p.453.

[xvi] Muir, John, 1912. The Yosemite. p.256.

[xvii] p. 239. Henry David Thoreau: Collected Essays and Poems. The Library of America, Literary Classics of the United States, New York, NY.

[xviii] p. 63. Lawson, John, 1709. A Voyage to Carolina; Containing the Exact Description and Natural History of that Country: Together with the Present State Thereof and a Journal of a Thousand Miles Travel’d thro’ Several Nations of Indians Giving a particular Account of their Customs, Manners, Etc. London, UK.

[xix] P. 54. Morton, Thomas, 2000. New English Canaan. Digital Scanning, Inc., Scituate, MA. Originally published 1637 in Amsterdam.

[xx] Statutes at Large, Thirty-Eighth Congress, Session I, Ch. 184, 1864. p.325.

[xxi] Statutes at Large, Forty-second Congress, Session II, Chapter XXIV. p.32.

[xxii] Meine, pp. 506-516.

[xxiii] Meine, p. 520.

[xxiv] Meine, p. 517.

[xxv] Meine, pp. 524-525.

[xxvi] The Nature Conservancy, nd. The Land & Water Conservation Fund: A Legacy for America.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.