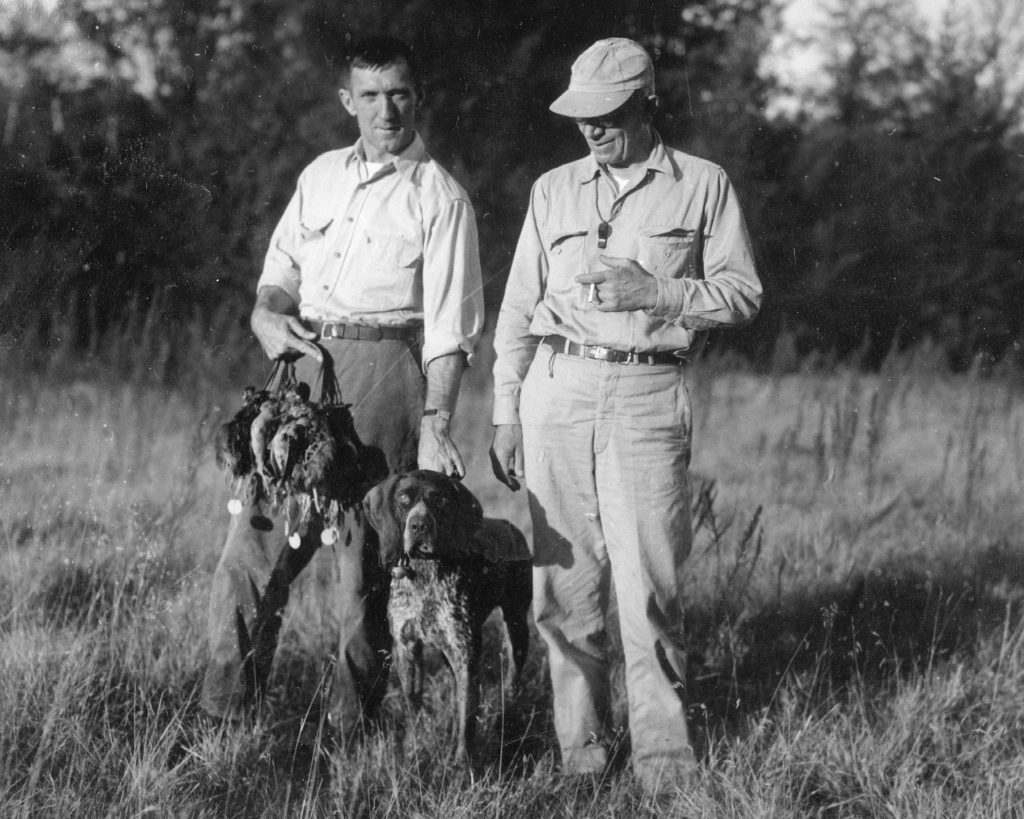

Aldo Leopold (right) and his last graduate student, Robert McCabe in the field during McCabe’s research.

In 2014, I was invited to give the keynote address for the annual meeting of the Mountain and Plains Chapter of The Wildlife Society, the organization of professional wildlife biologists. The situation on the conservation front was challenging then; it may be even more challenging now. Here are my remarks:

THE WORD “PROFESSIONAL” HAS BEEN SADLY COMPROMISED in recent decades. These days, it’s generally taken to describe someone who does what he does for money. Webster’s offers a definition I find more appropriate: “characterized by or conforming to the technical or ethical standards of a profession.” In some lines of work, this “conforming to the technical or ethical standards of a profession” begins with an oath. Medical doctors still swear to uphold the Hippocratic creed; attorneys take an oath to uphold the constitutions of the United States and the states in which they practice.

Wildlife professionals aren’t required to take an oath before they begin their practice, but I think we all agree that there is a code in our profession. The Wildlife Society has written some of it down in the organization’s code of ethics, which requires its members, among other things:

To use sound biological, physical, and social science information in management decisions;

To promote understanding of, and appreciation for, values of wildlife and their habitats;

And to uphold the dignity and integrity of the wildlife profession.

Like so many ethical matters, these precepts are relatively easy to set down in high-flown prose. They’re a lot harder to live by. In the typical Hollywood film or best-selling paperback, the approach of an ethical dilemma is foreshadowed in not-so-subtle dialogue; the moment of truth is announced with a fully orchestrated John Williams fanfare, and Bruce Willis or Mark Wahlberg or Jason Statham emerges victorious at the end, bloodied but unbowed, to the applause of an appreciative crowd, on-screen and off.

In the real world, none of that happens. Ethical dilemmas sneak up on us, camouflaged in appeals for compromise and heartfelt tales of economic hardship. The pivotal moment in the debate is generally buried in months of committee meetings, hearings, and white papers, and the professional who stands up on the side of sound information and transcendent values is as often vilified as praised.

In spite of those harsh realities, the wildlife profession has a proud history of standing up, a history that’s worth remembering when really troubling ethical questions arise. Here are three examples:

Olaus Murie and the campaign to eradicate predators

Olaus Murie was born in the spring of 1889 to Norwegian immigrants in Moorhead, Minnesota, a railroad town on the eastern edge of the northern prairie. His boyhood was tough by modern standards— from time to time, he boarded out to work on local farms, cut wood for money, and delivered milk to help support the family, but he also found time to indulge his passion for the outdoors in the prairies and timber along the Red River.

After he worked his way through Fargo State College and Pacific University, Murie went to work as a game warden in Oregon until he got the chance to join an expedition to Hudson’s Bay headed by an ornithologist from the Carnegie Institute in 1914. When the other members of the expedition headed home that fall, Murie stayed in the North without wages to continue collecting specimens over the winter. He learned the art of driving a dog team and picked up a scrap of the Inuit language in the process. He went south the following summer but returned to northern Quebec two years later for a second collecting expedition.

In 1920, he hired on with the Bureau of Biological Survey, forerunner of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to study the caribou herds in Alaska and the Yukon. He spent the next eight years in Alaska, doing wildlife research the old-fashioned way by living, almost year-round, with his subjects. He wrote the first major technical report on the caribou in the region before his bosses re-assigned him to Jackson Hole, where concerns had been raised about the health of the local elk herd.

Murie’s rise as a researcher with the Biological Survey came at a time when the agency had taken on a huge new function. The survey began in 1885 as the Section of Economic Ornithology in the Department of Agriculture. The unit owed its existence to the influence of the American Ornithologists Union, whose conservation committee had pressed the government to collect information on the food habits of birds in order to convince farmers that most birds didn’t eat crops but helped control the insects that did. With that background, the new unit spent more time on research than it did on pest control.

That began to change in the early 1900s as Congress pressed the agency for more tangible results. The leaders began research on using poisons against insects and issued publications on trapping and poisoning methods to control predators that were taking livestock. In 1915, the division, rechristened as the Bureau of Biological Survey, started its own trapping and poisoning program, with the stated intent of “destroying wolves, coyotes, and other predatory animals.”

In 1921, the year after Murie hired on with the bureau, federal trappers reported taking more than 24,000 coyotes, 694 wolves, and 129 mountain lions. It was estimated that another 25,000 to 30,000 coyotes died of the lingering effects of strychnine and were not recovered.

Congress was overjoyed. In 1923, the appropriation for predator control was more than $400,000, and bureau trappers claimed a scalp count of 25,000 coyotes, 599 wolves, and 158 lions. “In the campaign which has been waged for the destruction of timber wolves,” bureau chief E.W. Nelson reported, “most gratifying results have been obtained.” The kill on coyotes continued to rise— 34,000 in 1924, 37,000 in 1925— while the count on gray wolves dwindled— 202 in 1926, 47 in 1927.

In the 1920s, there weren’t many Americans who advocated complete protection of wolves and coyotes, but there were researchers in the scientific community who were concerned about what seemed to be a program to eliminate predators rather than controlling them around livestock. Dr. Lee Dice at the University of Michigan was one of the first to raise his voice against government-funded eradication efforts.

“I do not advocate that predatory mammals be encouraged nor permitted to breed everywhere without restriction,” he wrote in 1924, “but I am sure that the eradication of any species, predatory or not, in any faunal district, is a serious loss to science.”

Murie had observed wolves hunting caribou in Alaska and Canada and was convinced that the packs had little effect on the herds, regardless of popular sentiment among settlers who had recently come into that country. As part of his work in Jackson Hole, he had started a detailed analysis of coyote food habits to find out whether coyotes were taking an important toll on local elk. Again, he concluded that coyotes had little effect on elk.

In the spring of 1929, he wrote a five-page memo to the chief of his bureau, Paul Redington, considering the tone that the predator control program had developed:

“In the predatory animal division . . . there is constant effort to produce hatred. . . . It seems entirely unnecessary and undesirable to kill offending creatures in a spirit of hatred, call them “murderers,” “killers,” “vermin” in order to justify our actions. . . . Glaring posters, portraying bloody, disagreeable scenes, urging some one to kill, are working against the efforts of our other selves, who are advocating conservation, appreciation of wild life.”

He pointed out that the American attitude toward predators was changing: “Many people, as you know, are advocating a certain balance between predatory species and the game, merely that the predatory animals may have some small place in our fauna. I certainly think this is a reasonable request, especially where legitimate pursuits are not interfered with.”

Murie was criticizing a program that, in 1929 alone, attracted $559,000 in Congressional appropriations and matching funds of $1.8 million from states and livestock groups. I can find no record of Chief Redington’s reaction to the memo, but as a thirty-six-year denizen in the bowels of two state wildlife bureaucracies, I think I can guess what it was.

By 1931, Murie had collected more than 700 scat samples from coyotes in the Jackson country, along with sixty-four stomachs. With help from his brother Adolph, then at the University of Michigan, he analyzed these samples and prepared a manuscript to report the results. He finished his final draft during the winter of 1931-32 and circulated it to officials in the bureau as well as to outside experts like Dr. Joseph Grinnell, a mammalogist at the University of California-Berkeley.

The paper showed conclusively that coyotes were hardly eating elk or livestock— the overwhelming majority of their diet was voles and pocket gophers. Murie followed where the data led.

“Of the long list of items in the coyote’s year-long diet in the Jackson Hole country, 70.29 percent may be credited to the animal as indicating economically beneficial feeding habits; 18.22 percent may be classed as neutral, and only 11.49 percent may be charged against the coyote,” he concluded. “To sum up, the fur value of the coyote, the potential value of its beneficial habits, the fact that the animal is intrinsically interesting and has a scientific value, however much derided, can be given considerable weight. After all, the wildlife question must resolve itself into sharing the values of the various species among the complex group of participants in the out-of-door and wilderness wealth, with fairness to all groups. Under such considerations, with possible local exceptions, the coyote deserves to remain a part of the Jackson Hole fauna, with a minimum of control, and that only in the case of unusual local situations.”

Joseph Grinnell and other academics thought Murie’s research was sound and his conclusions, valid, but the reviewers at the bureau were not pleased. At least one official complained that Murie was not a part of the food habits research unit and, thus, should not be collecting scat samples, even to find out whether coyotes were eating elk. Another reviewer wrote that “Mr. Murie seems to favor the predator on every occasion possible.” The manuscript disappeared into the bureau’s central office and was not published until October 1935.

When the report finally appeared, the editor of Audubon’s Bird Lore, predecessor of Audubon magazine, invited Murie to write a popular article on his findings. When the bureau’s chief of wildlife research found out about the project, he wrote the editor: “In view of the comparatively limited experience that Mr. Murie has had with the coyote and the limitation in his study of the food habits and economic relationships of the coyote . . . the Bureau is not warranted in approving for publication at this time the article as submitted by Mr. Murie.”

Murie was also denied permission to present his findings at a technical conference that year.

After twenty-five years with the bureau, Murie resigned in 1945 to become the executive director of the Wilderness Society, his profound differences with the bureau’s leadership never resolved. Murie never offered a pubic explanation for his early departure, but it’s reasonable to believe that he left, at least partly, because of the abiding conflict with his administrators. Shortly after he resigned, he wrote to Clarence Cottam, who was serving at the time as associate director of the Fish and Wildlife Service, as the Biological Survey had come to be known.

“I know stockmen who are much more tolerant of coyotes that our Service is. I know many hunters who are much more tolerant. I know numerous people who would like to have a tolerant world, a world in which wild creatures may have a share of its products. Many people like to think of the beneficial side, the inspirational and scientific values, of creatures like the coyote, as well as the destructive side. This is the opposite of our official position.”

Olaus Murie. Professional.

Aldo Leopold and the deer wars

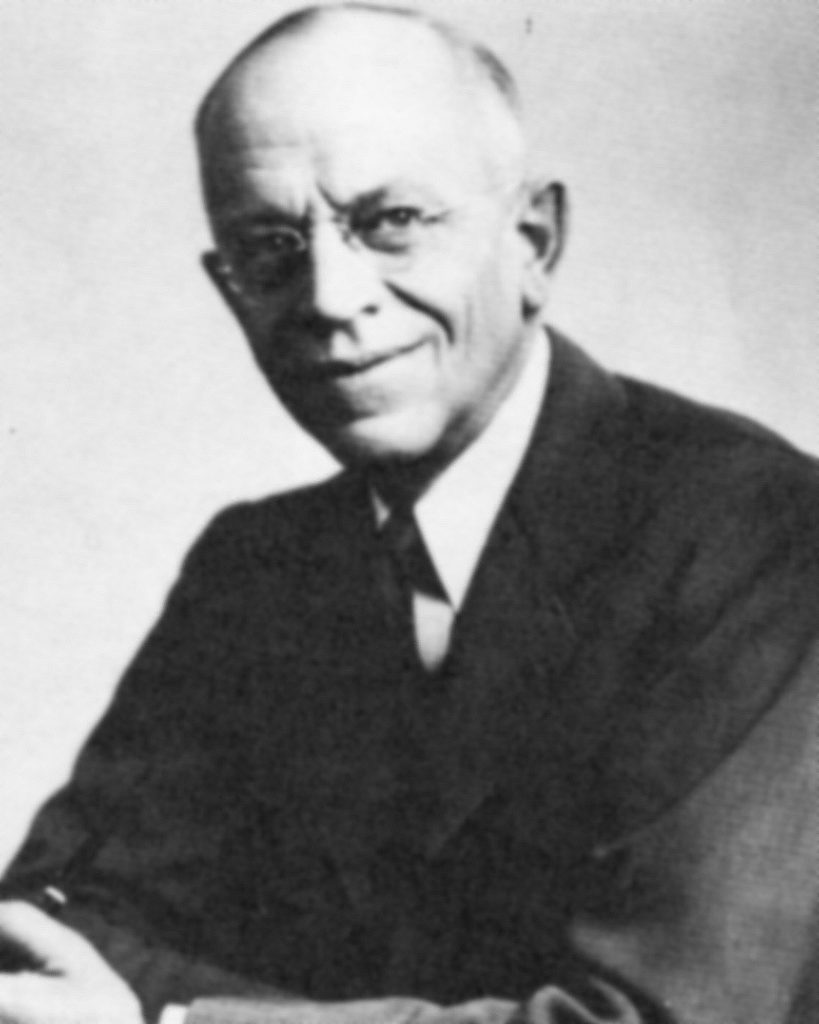

Aldo Leopold during his tenure as the first professor of wildlife management at the University of Wisconsin.

About the time Murie was deciding to part ways with the Fish and Wildlife Service, another confrontation over wildlife management flared up in Wisconsin with Aldo Leopold at its center. A contemporary of Murie’s, Leopold grew up in more comfortable circumstances in Dubuque, Iowa, hunting and fishing along the Mississippi with his father and brothers. His parents could afford to send him to prep school in New Jersey, and when the time came for college, Aldo chose Yale, primarily because of its newly established school of forestry, the brainchild of Gifford Pinchot.

At the time, Pinchot was presiding over the nascent U.S. Forest Service, and the Yale School of Forestry served as an academy to prepare young foresters for careers in his outfit. Pinchot laid heavy emphasis on the idea of “use” in the term “wise use.” His utilitarian approach to resource management put him at odds with men like John Muir, who emphasized the spiritual importance of wild places, but it fit well with political realities of the age.

Young Aldo finished at Yale in 1909 and immediately accepted an appointment on the Carson National Forest in New Mexico. His early positions on game management reflected his training and the prevailing attitude of the time. In 1915, he called for more appropriations to support the Bureau of Biological Survey in “the excellent work they have begun,” and as late as 1920, he wrote: “It is going to take patience and money to catch the last wolf or lion in New Mexico. But the last one must be caught before the job can be called fully successful.”

Hard to believe that, twenty years later, the same man could mourn the loss of the “fierce green fire” in a dying wolf’s eyes and write: “I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.” Like Murie, Leopold had the strength of character to re-examine his positions on key issues when the facts demanded it, the strength to change his mind.

Of the contentious issues Leopold addressed— the place predators deserved on the landscape, the importance of wilderness, the extension of the human ethical code to the rest of the natural world— none was as controversial or exposed him to such intense attacks as his position on deer management in Wisconsin.

Leopold had left the Forest Service for a job surveying game populations in the upper Midwest, a project that led to Leopold’s book, Game Management, and an appointment as the world’s first professor of game management at the University of Wisconsin in 1933.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, the forests in the northern and central part of Wisconsin began to recover from two generations of clear-cutting, and the young stands of shrubs and deciduous trees offered perfect food and cover for white-tailed deer. The combination of excellent habitat and stringent legal protection allowed the state’s herd to explode. As the second growth aged, reports of starving deer in the north country began to trickle in through the early 1930s. For several years, Leopold pressed the state’s conservation department to research the problem, but the department resisted until 1940, when a change in leadership and increasing mortality among deer finally resulted in a technical inquiry into the cause, which turned out to be a classic case of overbrowsing. In 1942, Leopold was appointed to a nine-member Citizen’s Deer Committee, charged with making an independent assessment of the deer situation.

Leopold had seen what too many deer could do to themselves and their habitat. He had been with the Forest Service in the Southwest at the beginning of the Kaibab debacle; he had done a detailed study of deer for hunt clubs in northern Michigan; he had watched with great interest as similar problems developed in Pennsylvania, and he had toured the intensively managed forests of Germany, dark stands of mature timber with no understory— and precious few deer.

In May, 1943, he reported the findings of his committee to the state’s conservation organization and recommended an antlerless-only deer season for the fall. He also suggested that the bounty on wolves be lifted and that artificial feeding efforts be curtailed. The cure for whitetails was straightforward in his mind— it was the management of people, not deer, that most concerned him.

“There is no doubt in our minds,” he wrote in his final report, “that the prevailing failure of most states to handle deer irruptions decisively and wisely is [due to the fact] that our educational system does not teach citizens how animals and plants live together in a competitive-cooperative system.”

He was about to find out how right he was.

As the deer season ended that year, opponents labeled it “the Crime of ’43.” In 1944, a group of incensed deer hunters formed the Save Wisconsin Deer Committee and began publishing a monthly newspaper. In the first issue, the committee identified the man they held responsible for the new management policy: “The infamous and bloody 1943 deer slaughter was sponsored by one of the commission members, Mr. Aldo Leopold, who admitted in writing that the figures he used were PURE GUESSWORK. The commission accepted his report on this basis. Imagine our fine deer herd shot to pieces by a man who rates himself a PROFESSOR and uses a GUESS instead of facts.” Another irate hunter wrote: “ Perhaps, the big mistake that has been made is the fact that we do not have an open season on experts.”

Leopold took this sort of public thrashing until his death in 1948 and never responded directly, preferring to refine and restate the case for antlerless deer seasons as a way of maintaining both deer and deer habitat, an approach that is universally accepted in the technical community today even though it’s still controversial in some sectors of the public, as many people in this room know all too well.

Aldo Leopold. Professional.

Rachel Carson and persistent pesticides

Not long after Leopold’s untimely death, another biologist made national headlines. She held a master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University and had worked her way up to a position as chief editor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service after a sixteen-year career translating the technical reports from the Service’s biologists and managers into plain English. Her name was Rachel Carson.

Widely respected for her skill as a writer, Carson had published one book, Under the Sea Wind, along with many popular articles on marine biology for major magazines, but she’d never made enough with her words to depend on them for a full-time living.

Until The Sea Around Us. Published in 1952, her book on life in the ocean rose almost immediately to second place on the New York Times’ best-seller list. Its success made her an instant celebrity and allowed her to take early retirement from federal service. The public looked to her for more charming, insightful words on the marvels of nature. What they got was Silent Spring.

I think most of us in this line of work think of Silent Spring as one of the most important environmental books of all time and rate Rachel Carson as one of the most influential environmentalists of the last century, all of which is true enough.

As we look back on the warm glow of her fame fifty years after Silent Spring first hit the streets, it’s easy to forget what the book cost its author.

Carson first became concerned about the side effects of the wide use of DDT in 1945, as researchers at the Patuxent Research Center began to study its effects on waterfowl and other birds as well as beneficial insects. She wasn’t against the use of pesticides entirely, but she was worried about their effects when they were used indiscriminately at a landscape scale. At the time, she couldn’t interest an editor in the subject, which was probably just as well, since anything she might have written at the time would have been scrutinized by federal officials before it could be published.

In 1957, on her own and with a national best-seller to her credit, Carson turned her attention back to the growing scientific literature on the effects of DDT and other pesticides. She began serious work on the subject the next year, while also looking after her terminally ill mother and an obstreperous grand nephew she had adopted after his mother’s death. The analysis of the technical literature and unpublished research on the effects of pesticides was a daunting task, both in terms of the sheer volume of emerging information and its technical complexity.

It was also politically sensitive. As the USDA’s Agriculture Research Service began to recognize Carson’s intentions, administrators tried to block access to information she wanted from the agency. She eventually got what she needed from people inside ARS who shared her concerns and leaked information.

Two years into the research and writing, she was diagnosed with an ulcer, followed by a bout of pneumonia and then, in the spring of 1960, breast cancer. She kept writing, often while in bed recovering from surgery, radiation therapy, and associated infections.

Even before the book was finished, friends warned Carson that she was courting controversy. Clarence Cottam, who had recently retired as director of the Fish and Wildlife Service, wrote to her in 1961: “I am certain you are rendering a tremendous public service; yet, I want to warn you that I am convinced you are going to be subjected to ridicule and condemnation by a few. Facts will not stand in the way of some confirmed pest control workers and those who are receiving substantial subsidies from pesticides manufacturers.”

Silent Spring was published on September 27, 1962, and the reaction from the chemical industry was immediate and intense. One company threatened legal action. Industry representatives and lobbyists arranged for an avalanche of complaints to the publisher, many of them anonymous. A biochemist with American Cyanamid wrote that “if man were to follow the teachings of Miss Carson, we would return to the Dark Ages, and the insects and diseases and vermin would once again inherit the earth.” He accused her of being “a fanatic defender of the cult of the balance of nature.” Her academic credentials were denigrated; her motives were questioned; her character was assaulted. Former secretary of agriculture Ezra Taft Benson is said to have written a letter on Carson’s book to Dwight Eisenhower, wondering “why a spinster with no children was so concerned about genetics.” He went on to speculate that she was “probably a Communist.”

Time magazine thought that “her emotional and inaccurate outburst in Silent Spring may do harm by alarming the nontechnical public, while doing no good for the things that she loves.” The National Agricultural Chemicals Association spent more than $250,000 attacking assertions in the book. Some members of the academic community were severely critical while others expressed tepid support.

It was a firestorm of corporate and bureaucratic outrage, and it came at a time when Carson was struggling with weakness and angina caused by repeated radiation treatments. In spite of her deteriorating health, she accepted several invitations to speak on the issue of pesticides, defending her work and conclusions quietly, but with passion and technical precision. In the spring of 1963, she was interviewed for an hour-long installment of CBS Reports, titled “The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson,” and in May, she gave testimony on pesticides before two committees in the U.S. Senate.

The cancer had metastasized into her bones and liver. By fall, she could barely walk, and as the new year dawned, she came down with a severe respiratory virus. On April 14, 1964, with the debate she had started still galvanizing the nation, she died. As for Silent Spring— before she died, she said that “it would be unrealistic to believe one book could bring about a change. But now I can believe I have at least helped a little.”

Rachel Carson. Professional.

The upshot

Three exceptional people but by no means the only exceptional people in this field. Over the years, I’ve known at least four who gave their lives in the line of duty and two others who came dangerously close. I’ve also known a number who’ve stood up when the standing was hard:

The group of biologists with the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks who stopped the proposal to dam the Yellowstone River. They won that fight, and after everyone else had declared victory and gone home, they were re-assigned and eventually eased out of the department. The Yellowstone remains the only major undammed, free-flowing river in the contiguous forty-eight states as a result of their work and sacrifice.

In 2003, A Wyoming Game and Fish biologist spoke at the North American Interagency Wolf Conference in Pray, Montana. The Wyoming legislature had just passed a wolf management law that ignored the Game and Fish Department’s recommendation that wolves be classified as trophy animals across the state. This biologist expressed the view that the legislature’s plan probably didn’t provide enough habitat to maintain a viable wolf population, which would land the wolves right back on the federal list of endangered species. He had the data to back up his position, but that didn’t matter much to Wyoming politicians. He was summarily placed on administrative leave, pending a review of his comments. It took an outcry from professional organizations and biologists across the region to return him to duty.

In 1983, that same biologist first pointed out the impacts a fence on Red Rim in the southern Wyoming desert would have on antelope and other big game. The fence was built by a wealthy Texan, who argued that the department was mismanaging the antelope. The biologist told reporters, “I’m morally responsible to those animals. It’d be tougher than hell for me to sit back and watch them die.” The landowner lawyered up and did his best to woo the state’s politicians to his side, but in the end, the fence came down.

In the 1990s, several biologists were swept up in the deer wars in southwestern Wyoming as local herds were devastated by almost a decade of drought. Often undercut by their own leadership, these men continued to emphasize the relationship between deer and forage, pointing out again and again that you can’t have any more deer than the habitat will support. I think they laid the groundwork for the calmer, more productive conversations that characterize deer management in the state today.

Then there were the confrontations over mined land reclamation, instream flow, and John Dorrance’s exotic game farm, the call for an end to sage grouse hunting.

There’s no doubt that an employee owes a certain degree of loyalty to his employer. In Wyoming, it’s popular to say that we should always “ride for the brand.” But there are other loyalties to be considered. The Wildlife Society’s code of ethics states that its members should “recognize the wildlife professional’s prime responsibility to the public interest, conservation of the wildlife resource, and the environment.”

Our “prime responsibility.”

I can’t say how far that responsibility should carry any professional. These are dangerous times in conservation— the public constituencies that once supported enlightened wildlife management are increasingly divided and often caught up in their own self-centered demands, which makes it harder for a biologist to speak truth to power. But, as hard as it may be, it is still the most important part of the biologist’s job.

It’s often said that, as professionals, we need to pick our battles, and I agree with that, since it suggests that there are some battles worth fighting. And I would go further: There are some battles worth fighting, even if there’s a chance we’ll lose. Sometimes, a loss prepares the way for a victory. A classic example was the struggle to stop the Glen Canyon dam on the Colorado River. Conservationists eventually lost that fight, but the high-profile public debate on the issue changed the American view on dams and headed off another dam proposal that would have flooded the lower part of the Grand Canyon.

Professional wildlifers have worked miracles across America and here in the mountains and plains, often at great personal sacrifice. You are the bearers of that proud tradition. It can be a heavy load, but one well worth carrying. I’ve always liked Teddy Roosevelt’s view of the matter. “Far and away the best prize that life has to offer,” he told a crowd in 1903, “is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.” You have that chance. Make the most of it.

And my deepest thanks for all you do.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.